| Bekijk deze nieuwsbrief in uw browser. | |

| Klinkende overwinning: Grondwettelijk Hof fluit Vlaamse Regering terug in KinderopvangzaakOuders die samen minstens 4/5e werken, of een dagopleiding volgden, kregen voorrang in de kinderopvang. Vandaag heeft het Grondwettelijk Hof beslist dat deze voorrangsregel discriminerend is en vernietigd wordt. "Dit is een megazotte overwinning die we hebben behaald", aldus de Kinderopvangzaak. "Het Hof bevestigt dat kinderopvang een recht is en niet een privilege." Lees verder |

| Toen ik mijn smartphone verloor en mijn wereld plots tot rust kwamAltijd verbonden, altijd beschikbaar. De gsm is een perfect product van onze samenleving, die maar één ding lijkt te schreeuwen: wees productief! Lees verder |

| "Aantal omwonenden Zwijndrecht met te hoge PFAS-waarden, hoger dan huidig bloedonderzoek uitwijst"1 op de 2 geteste inwoners in Zwijndrecht, waar de 3M-fabriek staat, heeft een te hoog PFAS-gehalte in het lichaam. Dat blijkt uit het bloedonderzoek georganiseerd door de Vlaamse regering. Burgercollectief DARKWATER3M vindt dit al alarmerend. Bovendien zijn hier volgens hen nog oude normen gehanteerd en wekt de regering zo de indruk dat het de verontreiniging en de effecten op de volksgezondheid wil minimaliseren. Lees verder |

| Het Polen-moment van ArizonaDe aanval van de regering-De Wever op de Raad voor Vreemdelingenbetwistingen is niet minder dan een bedreiging voor onze rechtsstaat. Dat zijn grote woorden, maar ik spreek ze niet lichtzinnig uit. Lees verder |

| Jo Cottenier: rebellenhart, scherpe geest – afscheid van een rode pionierVan de Leuvense studentenprotesten tot de mijnen van Genk, van anti-imperialisme tot klimaatstrijd – Jo Cottenier stond altijd aan de kant van de werkende mens. Een leven lang gaf hij vorm aan een radicale, consequente linkerzijde in België. Lees verder |

| Overleven op het ritme van de elektriciteit in MaliUit Mali bereiken ons de afgelopen jaren steeds onheilspellendere berichten: klimaatverandering, jihadistisch geweld, militaire coups, diplomatieke spanningen met het Westen, de komst van Russische paramilitaire Wagner-troepen (nu Africa Corps), noem maar op. Achter deze krantenkoppen gaat het leven gewoon verder in het West-Afrikaanse land. Lees verder |

| Ombudsrail-rapport 2024: beterschap maar nog veel onwil bij NMBSDe ombudsdienst voor de treinreizigers Ombudsrail publiceerde zijn jaarrapport 2024. De NMBS gaat enigszins beter om met klachten, maar blijft nog hardleers. Fouten toegeven of excuses aanbieden is nog steeds een brug te ver voor onze openbare treindienst. Lees verder |

| |

| Burgerjournalistiek, powered by DeWereldMorgen.be | |

Israël blokkeert al bijna twee maanden toegang tot voedsel en noodhulp voor GazastrookIn een open brief roept Standpunt Palestina Solidariteit de federale regering op tot actie. Sinds 2 maart blokkeert Israël alle toegang tot voedsel, medicijnen, brandstof en noodhulp voor de Gazastrook. Deze week herhaalde Israël dat de blokkade blijft zolang niet aan zijn eisen is voldaan. "Federale ministers, waar wachten jullie op om actie te ondernemen?" Lees verder | |

SPREAD THE INFORMATION

Any information or special reports about various countries may be published with photos/videos on the world blog with bold legit source. All languages are welcome. Mail to lucschrijvers@hotmail.com.

Autobiography Luc Schrijvers Ebook €5 - Amazon

Search for an article in this Worldwide information blog

woensdag 30 april 2025

WORLD WORLDWIDE EUROPE BELGIUM BRUSSELS - dewereldmorgen magazine - progressieve media - Woensdag 30 april 2025.

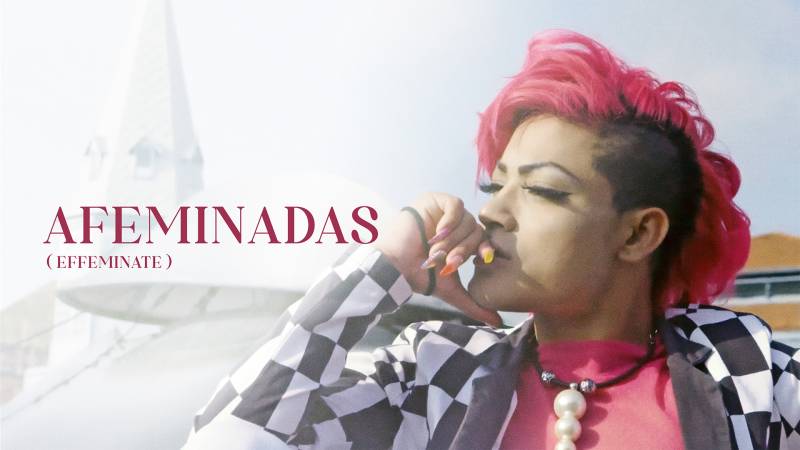

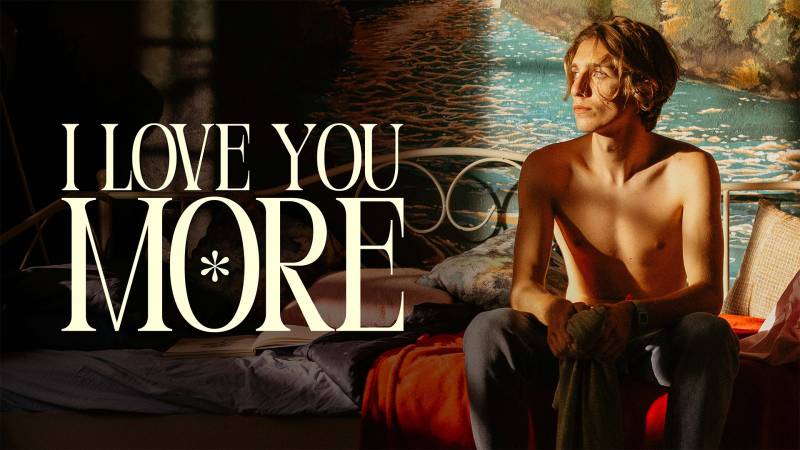

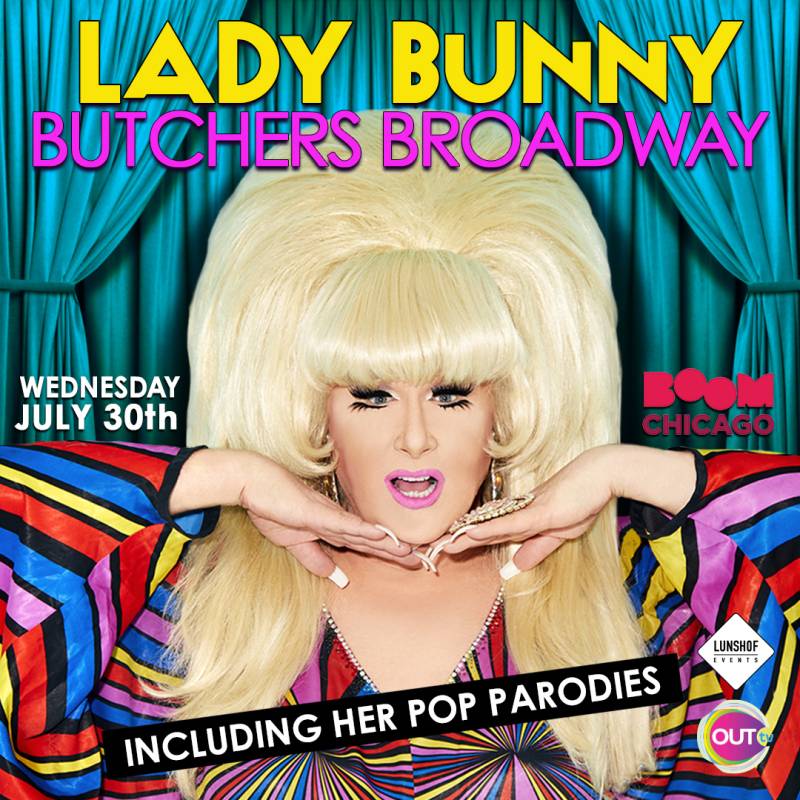

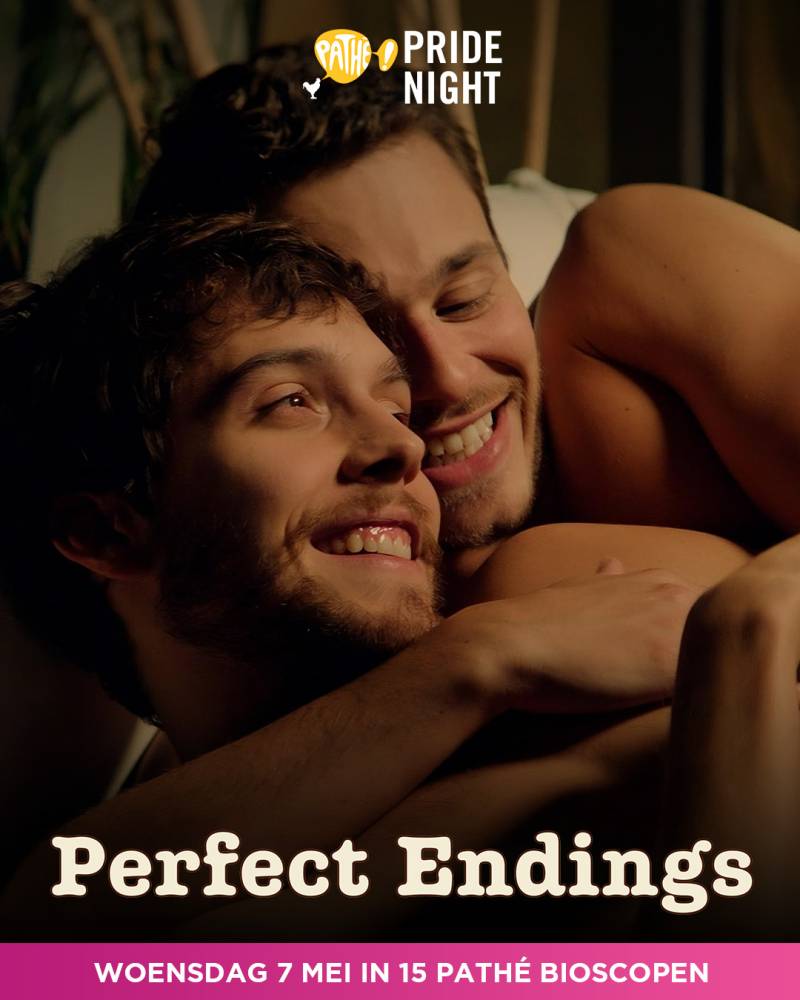

WORLD WORLDWIDE EUROPE THE NETHERLANDS - OUTtv Update 💌: Mei bij OUTtv - LGBTQIA+ Homosexualité GAY - Program from 30 April 2025.

|

Abonneren op:

Reacties (Atom)