Weather watchers may be more preoccupied of late with storms popping off in the Gulf of Mexico and the eastern Pacific, but a very unusual cyclone also spun up over the Arctic this week—and it could spell more bad news for the region’s ailing sea ice.

The Arctic is no stranger to cyclones, but the latest no-name storm, which emerged in the Kara sea north of Siberia, has garnered attention both for its size and timing. The storm’s central pressure (a measure of its strength) bottomed out Thursday at about 966 millibars, placing it par with the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012, one of the most extreme summertime storms in recent memory. That storm reached a minimum central pressure 963-966 millibars, depending on which analysis you trust.

The new storm’s occurrence in June is also noteworthy. Big cyclones like this don’t normally start hitting the Arctic until late summer. The Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 spun up in August as did a major storm in 2016.

“Preliminarily, this storm could rank in the Top 10 for Arctic Cyclones in June as well as for the summer (June through August) in strength,” Steven Cavallo, a meteorologist at the University of Oklahoma, told Earther via email.

Xiangdong Zhang, a scientist at the International Arctic Research Center who specializes in Arctic cyclones, cited a few factors responsible for the storm’s formation, including low sea ice cover in the North Atlantic which has increased the amount of heat in the atmosphere, a strong temperature gradient between land and sea, and the stratospheric polar vortex, an area of low pressure just above the storm.

“The downward intrusion of this polar vortex intensified [the] storm,” Zhang told Earther via email.

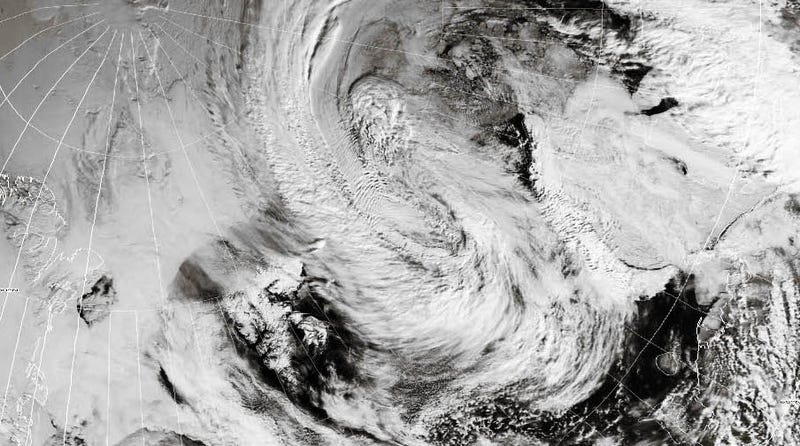

The no-name storm reached peak photogenicity yesterday, with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration capturing a stunning high-resolution image.

While your typical late-season Arctic cyclones are notorious for chewing up sea ice, what this early season beast will mean for ice remains to be seen.

“This storm is very quick-moving and occurring earlier in the season,” University of California, Irvine Ph.D. candidate Zack Labe told Earther via Twitter direct message. “Its impacts to sea ice are likely not comparable to these other strong cyclones that have occurred later in the summer.”

Labe noted that early summer storms can favor cooler, cloudier conditions, slowing down the loss of sea ice, which typically bottoms out in September. However, he added that a storm of this strength “may precondition the ice for easier melt later in the season.”

Zhang said that due to the storm’s location, it can transport more sea ice out of the Arctic through the passage between Greenland and Svalbard known as the Fram Straight. “This will contribute to Arctic sea ice decrease, in particular thick ice,” he said.

Storm or no, it’s been a weird, bad year for Arctic sea ice so far. After limping along all winter, Bering sea ice was basically gone by May, months ahead of schedule. Even before this storm, sea ice around Svalbard was looking more like it should in September. Overall, Arctic sea ice extent for May was at its second-lowest on record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center’s latest monthly sea ice report released on June 6.

The role of rising temperatures in driving down sea ice is well established. But there’s also growing evidence that climate change could fuel more ice-shredding cyclones. Research going back to the early 2000s suggests Arctic cyclone activity is on the rise. And a study published in April concluded that these storms will become more frequent and intense in the future as the contrast between land and sea temperatures continues to rise.

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten